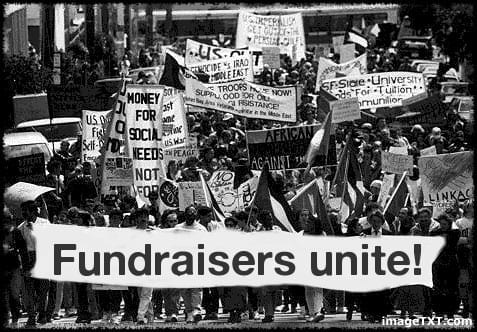

Should fundraisers strike? Why fundraisers need a collective voice

“Fundraisers should go on strike,” someone told me at the IoF Convention last week. She was only half joking.

I’m not suggesting that fundraisers should strike. But I am suggesting that they consider it. Because the process of considering a strike will require collective action and collective thought. It will throw up dynamic individuals who are prepared to challenge the current leadership by fronting a collective voice that speaks in defence of fundraisers.

[quote align=”right” color=”#999999″]’The voice of a ‘National Union of Fundraisers’ would have been heard loudly over the past couple of months'[/quote]

Not in defence of fundraising – the profession; but in defence of fundraisers – the people that actually do the job. Because a profession is nothing without the professionals who perform the role.

Yet while the world and his wife currently has a view on what’s wrong with fundraising and how it can be put right, the only group that doesn’t seem to have a collective view on what’s going on right now are fundraisers themselves.

Fundraisers can’t be trusted – or so it seems

NCVO waded into the debate a few weeks ago with Sir Stuart Etherington stating that fundraisers were ‘overfishing the waters’ (note that’s fundraisers specifically, not charities generally) and making some off-the-cuff recommendations about how self-regulation should be reformed. Now the Prime Minister has announced that Sir Stuart will lead the review of self-regulation.

I welcome NCVO’s involvement, I honestly do, and this review might just provide the breathing space needed to let everyone calm down and make some considered decisions.

[quote align=”right” color=”#999999″]’It must be very hard to feel proud to be a member of the fundraising profession when everyone seems to be criticising you, no-one seems to trust you, and no-one is speaking up in your defence'[/quote]

I just wish NCVO could be bothered to engage with fundraising at times other than when the government is taking an active interest. The last time NCVO made any significant contribution to fundraising was during Lord Hodgson’s review of the Charities Act 2006 in 2012. It’s been virtually silent in the subsequent three years. And yet as soon as the government is demanding change, NCVO magically rekindles its dormant interest in fundraising.

It’s almost as if NCVO is saying to fundraisers that you’re allowed to manage your own affairs providing there aren’t any really important issues, and then the big boys will step in and do things properly. It’s as if NCVO thinks fundraisers can’t be trusted to manage their own affairs.

And they’re not alone in that – neither does the Institute of Fundraising.

The IoF is reforming the standards committee to ensure that professional fundraisers hold a minority of the seats. This means that most of the people who set the professional standards that all fundraisers must follow will not be professional fundraisers.

What message does this send? To me it sends a distinct message that the Institute of Fundraising does not trust fundraisers to devise and run their own professional standards (and I have heard one senior fundraiser say as much in an unguarded moment).

One fundraiser I know told me that she could not comment publicly about current issues because her comms team had forbidden it.

This is another indication of the lack of trust placed in fundraisers – this time that they can’t be trusted to articulate an opinion on matters that affect their profession for fear of damaging the reputation of the charity they work for.

It also speaks to whether fundraisers have true professional autonomy – which is often seen as a key characteristic of professionhood. Professional autonomy means professionals have the freedom to exercise their own judgement in making professional decisions without being beholden on any other stakeholder. And yet here are fundraisers being forbidden from expressing opinions on the important matters that affect the future of their own profession.

It must be very hard to feel proud to be a member of the fundraising profession when everyone seems to be criticising you, no-one seems to trust you, and no-one is speaking up in your defence – and even when someone does, they are shouted down as refusing to accept the reality of current public opinion.

And so I repeat the question. Who is representing fundraisers in the current debate?

Who speaks for fundraisers?

It’s not the Institute of Fundraising. The IoF is currently representing the overall practice of fundraising and attempting to preserve its own central role in self-regulation.

The IoF presents itself as a professional institute. Institutes are composed of and are supposed to represent individual members. And yet for as long as I have been involved in fundraising, the Institute has acted as if it is a trade association representing its industry subsector and the needs of its organisational members.

The Institute of Fundraising has only been so called since April 2002. Before that, from its formation in 1983, it was called the Institute of Charity Fundraising Managers (ICFM). The ICFM included in its name the professionals it represented – fundraising managers. After the rebrand, it didn’t. Instead the name represented the role, but not the people who performed the role.

[quote align=”right” color=”#999999″]’For as long as I have been involved in fundraising, the Institute has acted as if it is a trade association rather than a professional institute'[/quote]

The rationale for the rebrand was that the Institute wished to acquire members in arts, education and healthcare fundraising who might not see themselves as ‘charity’ fundraisers. The ICFM board could have chosen the name ‘Institute of Fundraisers’, but didn’t, and the EGM that approved the name change heard that the new brand would allow the Institute to be “active wherever fundraising is an issue”.

In my capacity as editor or Professional Fundraising, I put it to the then CEP of the IoF, Lindsay Boswell, that the new Institute of Fundraising (but not Institute of Fundraisers) would sometimes find itself with a conflict of interest in trying to represent the needs of the industry and the needs of individual professionals, since the two may not always coincide and may sometimes even be in opposition. Lindsay replied that by representing fundraising, the Institute would automatically be representing the needs of fundraisers, because the two were the same.

I didn’t buy that then and I don’t buy it now.

For example, the needs of the IoF’s larger organisational members – those that are geared up for industrialised individual giving programmes – are served by a culture that promotes cheap, high volume donor acquisition. This need is manifested by high short-term targets that are often outsourced to agencies and managed by relatively junior fundraisers, often working long hours of unpaid overtime. Whole campaigns are often under-resourced (because there is always another agency that can do the job as cheaply). The result is that some agencies cut corners in a panic to meet the terms of their contracts and junior fundraisers leave their jobs within 18 months (for which we blame the fundraisers for being insufficiently committed rather than asking what’s gone wrong with the management process).

A body representing fundraisers might well argue that the needs of its members were better served by them not having to meet such under-resourced, high-pressure, short-term targets, and by having better working conditions. A voice representing fundraisers could well argue that that there is a need to shift the culture from cheap acquisition to a strategy based on recruiting higher quality donors who will stay giving for longer (which would cost more money initially but deliver better net income overall).

It’s not easy for a single organisation to represent both poles of this position.

Advertisement

Time for fundraisers to mobilize?

Who is standing up for professional fundraisers? (Composite image: UK Fundraising)

Adrian Sargeant and I both believe that fundraising would be better served by the code of practice being set by a body such as the Committee of Advertising Practice (CAP), which sets the codes for the advertising industry. Sir Stuart’s review may well recommend something like this.

If it did it would be excellent news for fundraisers, because it would mean that the Institute of Fundraising, relieved of its duties to set professional standards, could concentrate on representing the needs of its core stakeholders. Of course, it would have to choose whether its core stakeholders were individual members or organisational members: in other words, decide once and for all whether it is a trade association or a professional institute.

Whichever way the IoF swings, it will leave a vacancy that will need to be filled. If the IoF decides that it is a professional institute, then we will need a trade body that represents fundraising charities and fundraising agencies.

If the IoF decides that it really wants to be a trade association, then fundraisers will need to mobilize to ensure they have in their corner an organisation that will without fear or favour represent and stand up for professional fundraisers. Maybe they need to do that anyway.

I can’t imagine for a second that the voice of a ‘National Union of Fundraisers’ would not have been heard loudly over the past couple of months.

Ian MacQuillin is director of Rogare, the fundraising think tank at Plymouth University’s Centre for Sustainable Philanthropy.

Main image: workers on strike by ProStockStudios on Shutterstock.com