Time we ditched fundraising’s personality cult

Ian MacQuillin argues that fundraisers’ focus on personalities rather than what they say is stifling the culture of criticism we must have in place to rebuild the fundraising profession following the events of our sector’s annus horribilis.

One of our sector’s ‘gurus’ was delivering the opening plenary at a conference not so long ago.

This was how it was billed in the conference brochure. He was described as a “visionary” and “provocateur”. We were told he had energy, passion and that he was an original thinker. None of the foregoing, incidentally, is untrue. We were told that his session would be “fast-paced” (I’ve been to his sessions; they are). We were then invited to come and hear him “live and unleashed!” (exclamation mark in original).

Advertisement

The 113-word description of the opening plenary devoted most of those words to talking about the presenter, not about what he was actually going to say.

Which highlights something that’s niggled me about our sector for a while – quite a while – but I’ve not really been able put my finger on why until the events of recent months brought it into focus.

We have a cult of personality in fundraising. I don’t think I’m saying anything surprising or controversial here. There are a few – probably just a handful – of dominant individuals (almost all male) who tend to monopolise the conference circuit, and they are in great demand.

There’s nothing necessarily wrong with this: if they’ve got great ideas and deliver them brilliantly, why wouldn’t you want to go see them and why wouldn’t conference organisers want to put them on? And I don’t think it means fundraising’s élite are keeping out other conference speakers (though I do think this is something we ought to be vigilant of – many conferences plenaries are being delivered by the same people who did them when I entered the fundraising sector in 2001).

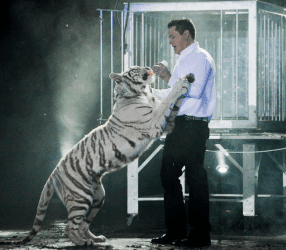

The issue is that we care more about who they are than what they say. Take the conference plenary description I opened this blog with. You are being exhorted to come to the plenary because of who the speaker is, not what he is going to say, and in language that motivates you for a showbiz experience rather than a learning one – “live and unleashed!”, he’s not a bloody celebrity magician with a Siberian tiger as his on-stage sidekick.

This wasn’t the case with the closing plenary speaker, a much less well-known name: most of the text outlined what he was going to talk about.

This is just one example (and I’ve not mentioned the speaker by name because he didn’t asked to be described this way – at least I assume he didn’t). But there are other instances where the focus has been on the messenger and not the message. Comments to sector blogs regularly start with a (sometimes fawning) appreciation of how great the blogger is – sentences such as: “I always look forward to reading your fantastic blogs”, or “once again you have enthralled me with your wonderful storytelling” (I made these up, but I’ve seen examples like them).

So what’s wrong with this? After all, it’s just people being nice to each other.

Stifling a culture of critique and criticism

The problem is that focusing on the person and not what they say doesn’t encourage a culture of critique and criticism. When so many people are lionizing fundraising’s great and good, any can criticism come across as a personal attack. And this is a very small sector, so you wouldn’t want to be seen as criticising someone whom everyone else is lauding.

You might even reason that doing so could actually cause you harm. If you are seen or heard to disagree with so-and-so or whatshisname, then you could infer that people will think you don’t know what you are talking about, and so you’ll keep your opinions to yourself.

Note that the problem would not be that the person doesn’t want to be seen to criticise whathisname’s ideas; but that she doesn’t want to be seen to criticise whatshisname the person. It could result in a kind of self-censorship that means new and exciting ideas don’t get the airing they deserve because no-one wants to criticise – dare I say, offend against – the people who proscribe received fundraising wisdom.

“We need to challenge everything. If something is good enough, it will emerge from the criticism, probably strengthened. If it doesn’t, it probably wasn’t such a good idea in the first place.”

When people do challenge the accepted consensus – one particularly strident critic of relationship fundraising who lives in Australia comes to mind – it’s too easy to dismiss them as lunatics shouting from the fringes, rather than respond to their criticisms, partly because the challenge is seen as a personal attack against the main proponents of the received consensus.

And there are times when people ought to be held accountable for the views they hold and the decisions they have taken.

On The Agitator earlier this year, Roger Craver namechecked the British Red Cross’s Mark Astarita in blog that was highly critical of role of the British fundraising leadership cadre in responding to the events following Olive Cooke’s death, prompted in this case by GoGen’s closure. Some of the ensuing Twitter traffic stated that it was wrong for Astarita’s name to be dragged into the discussion.

I’m not taking sides in the actual argument raised in Craver’s blog – that’s not the point of referring to it. But it seems fair to me that when fundraising directors of the biggest charities in the country are taking decisions (or failing to take decisions) of such vital importance, that they should be prepared to be challenged on those decisions, and to be available to publicly account for them and take personal responsibility for them.

We would expect business leaders to take responsibility for and explain to the public and the media their decisions. At the time Craver’s blog appeared, supermarkets were in the news for their pricing policies for milk, with farmers demanding a fairer deal. I don’t think we would expect that the ceo of Tesco or Lidl, say, should not have personally to account for the actions of their companies. In the same way, fundraising directors should not expect to ‘have their names kept out of things’ when things are going a bit pear-shaped.

We are left with an asymmetric arrangement:

When things are going well, fundraising’s leading figures are fêted and lionized to a degree that stifles genuine critique and criticism.

When things are not going so well, we think those same leading figures should be exempted from any personal accountability or criticism, and we self-censor to ensure this happens (I know I’ve done it).

It’s not personal, it’s the advance of reason

I suspect that part of the reason that fundraising is in the mess it currently finds itself in has something to do with the previous two statements. As a sector, we have failed to challenge the accepted way of doing things because we have been too focused on personalities rather than on what those personalities say or do; we have been too concerned that we say the right thing (what everyone else is saying) and avoiding saying the ‘wrong’ thing (which is perhaps what we should have been saying).

As fundraising rebuilds itself with new reviews, enquiries and commissions, we must ensure we don’t repeat this mistake. We need fresh ideas and thinking. We need to challenge everything. Nothing should be off-limits to critique and criticism and none of the accepted wisdom should be held so sacred that it is beyond question. If something is good enough, it will emerge from the criticism, probably strengthened. If it doesn’t, it probably wasn’t such a good idea in the first place. (The process I am describing in the method of enquiry we practice at Rogare and call ‘critical fundraising’).

No-one should consider themselves beyond having their ideals and principles challenged. And no-one should be afraid to challenge them.

As we go forward, we must understand that it’s what people say that matters, not who says it – the best solution to rebuild fundraising could come from someone none of us has ever heard of. And when we do criticise the arguments or opinions of so-and-so or whatshisname, all of us, including so-and-so or whatshisname, must realise that this is not personal, it’s simply the advance of reason and debate within our profession.

Ian MacQuillin is director of Rogare, the fundraising think tank at Plymouth University’s Centre for Sustainable Philanthropy.

More from Ian MacQuillin

- Same as it ever was – fundraising and the media (12 June 2015)

- Does fundraising need an ethics committee? (30 May 2014)

- Are you really proud to be a fundraiser? A new manifesto for fundraising (11 April 2014)