Measuring satisfaction: why charities ignore the customer at their peril

New rules around data and privacy. Unprecedented public and media scrutiny. Tighter budgets and greater competition. These are testing times for organisations, in the not-for-profit and private sectors alike. We are all being asked to do more with less. Not least, with the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) coming into force next month, the challenges of engagement will only grow.

At pivotal times like these, charities need more than just a clear strategy, vision and strong leadership; they also need an unwavering focus on their customers, be they service users, staff, volunteers, regulators or donors. Indeed, a steadfast commitment to good customer service – the holy grail of any thriving business – is key for success in the charity sector as well. Only through good customer service can loyalty be achieved.

And loyalty, of course, is the ultimate prize. But that service, for it to be truly valuable, needs to be measured, and it needs to be actionable.

Advertisement

Every organisation has promises it must keep to its most important constituents. Whether this is a service user or a museum visitor, their loyalty is testimony that an organisation is delivering on its commitment and will engender devotion, repeat business, and a solid reputation.

And just as in the hard-nosed business world, retention and repeat business are essential. After all, all good marketers knows it costs appreciably more to recruit customers and supporters than to retain them, and a long-term relationship offers a host of other advantages.

Loyalty, however, must be earned. In particular, with GDPR coming on line, sources charities may have previously used to build a prospect mailing list may no longer be viable, and the way an organisation interacts with the public will change dramatically. Communications must truly be strong and relevant, as people now have to opt in to mailings and solicitations in a way they’ve never had to before, and satisfaction will trade at an unparalleled premium.

At American Express, we recently asked consumers in 12 countries how well they feel companies serve them. More than seven in ten people said they are more likely to give an organisation repeat business if they receive good service, with a similar number saying they would on average tell 20 people about their good experience.

The same holds true for the third sector: an endorsement from a satisfied visitor or service user is an invaluable asset, boosting the collective influence of a charity’s most dedicated supporters.

Conversely, loyalty and reputation can be lost in a flash. If an organisation doesn’t deliver on a promise, if it is seen to violate trust and confidence or betray the charity’s values, clients and donors will drain their support in a heartbeat. And, as we’ve seen all too often recently, the media will pounce. As the fabled investor Warren Buffet has said, “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.”

The better a charity’s interaction with service users and donors, the stronger the relationship becomes; the more likely, too, they will be to return, to advocate and to donate. That means that every performance, exhibition, use of service, Facebook post or bucket collection in a draughty railway station has to be seen as an opportunity to provide strong customer service.

Measuring success

If every interaction is an opportunity to build and strengthen the bond with key constituents, then those interactions, and the satisfaction they engender, must be measured.

In business, companies measure everything. It’s in their DNA to survey their customers to ensure satisfaction, and there’s no reason that charities can’t and shouldn’t do the same. The methods used to measure satisfaction needn’t be prescriptive, but they should be rigorous, consistent, and above all actionable.

First, the organisation needs to define measurable performance indicators that can be used to assess whether the charity is meeting its mission and the needs of its stakeholders. These can be numerical measures such as repeat donation levels, service provision, website visits or social media engagement, as well as qualitative factors measured through surveys, for example whether donors would recommend a friend (a standard measure in business), if service users feel their communications are handled promptly and efficiently, or whether staff and volunteers agree that the charity is delivering on its mission.

But there’s no point seeking feedback for the sake of it; this insight must be used to make improvements and – too often neglected – communicated back to the people who provided comments in the first place.

And this process must genuinely be embedded in an organisation’s culture.

Many charities already do this exceedingly well.

• At the V&A Museum, for instance, feedback is actively solicited from visitors, which is regularly reviewed by management and the Board. In 2017 alone the museum received close to 3,000 trackable pieces of feedback, which are then classified as “comments, complaints and compliments.”

Everything from customer service of visitor-facing staff to how objects were displayed in an exhibition are assessed and benchmarked.

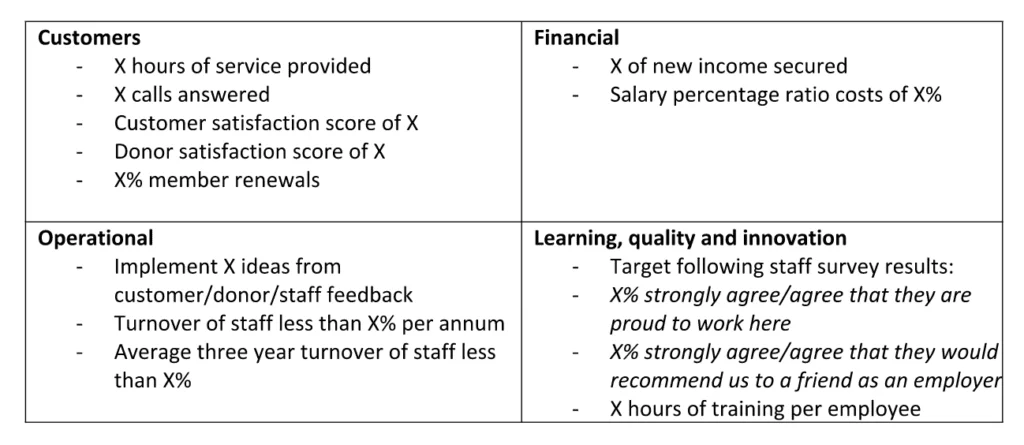

• At the Terrence Higgins Trust, the Board reviews a “balanced scorecard” of key service metrics against its objectives on a quarterly basis. There are almost 30 measures, including financials, operations and, not least, an external category which tracks client and funder satisfaction.

• At Sadler’s Wells Theatre, membership and development teams regularly send out emails after shows to get feedback on elements of presentation, the welcome and facilities at the venues.

These approaches to measurement may seem onerous and complicated, especially for smaller charities, but they needn’t be. And there is certainly no one-size- fits-all solution. At the Terrence Higgins Trust for instance, there’s a simple traffic light system (red, amber, green) to identify results that are within or outside target levels.

If formal text or automated telephone surveys are not the right approach for a charity, there are other, more ad hoc processes available to capture feedback, including training front-line staff to be alert to picking up valuable insight from their conversations with service users and donors. Even something as tried-and-true as a centralised inbox for suggestions and comments can help to identify trends as they emerge.

The key to it all is to ask the right questions, tailored to different audiences, so that the findings can help allocate valuable human and financial resources to achieving service delivery and fundraising targets.

Finally, with charities under increasing public scrutiny, transparency, integrity and accountability are more and more important. That means that, if every customer interaction is really to count, charities shouldn’t shy away from talking about how they track satisfaction and the actions they put in place as a result.

Proactively sharing a publishable version of a balanced scorecard, for instance, is a valuable way for a charity to demonstrate it is taking performance seriously, and that its customers, in all their guises, are at the heart of the organisation’s culture.

Robert Glick is Vice President of Corporate Communications at American Express and a Trustee of various UK charities, including the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Terrence Higgins Trust and Sadler’s Wells Theatre.