It’s time that fundraisers started taking Darwin seriously

A recent joint study by researchers at Oxford and Kent universities has found that men are likely to give more money if they are asked while they are in the company of women they find sexually attractive. In fact, they were between 25 per cent and 100 per cent more generous when they were in the presence of women they wouldn’t have minded getting off with.

This is clearly pretty big news for fundraisers, wouldn’t you say? I mean think of all the ways you could assimilate this thinking into your fundraising. That’s not a rhetorical question; think about it.

And yet this story received only cursory coverage in just one charity sector publication, and that was in the ‘…and finally’ slot, the bit that’s reserved for all the quirky, left-field, off-the-wall stories that are fun but you don’t take all that seriously.

Advertisement

I think the lack of coverage in the sector press is a reflection of the way the fundraising sector views a certain subject.

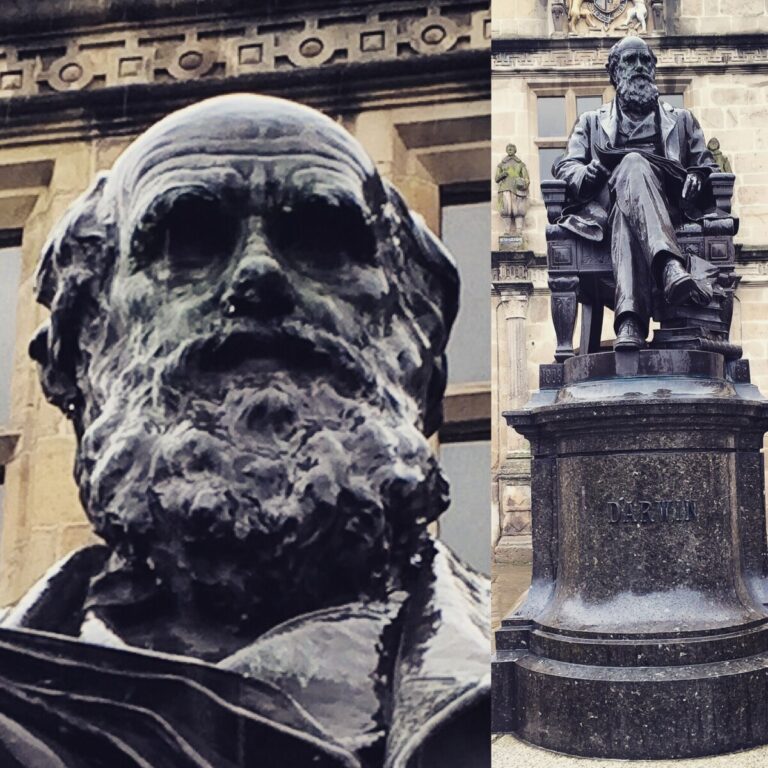

The Oxford/Kent study was led by Oxford’s Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology, so this research is firmly rooted in modern Darwinian thinking. (It’s basically suggesting that men think that appearing more generous will help them get to have sex – and we didn’t know this already, eh?)

Do fundraisers ignore Darwin?

Darwinian thinking, however, is something fundraisers seem to go out of their way to avoid and I can think of only three people in this sector who have ever really tried to incorporate any kind of Darwinism into their ideas about fundraising.

Most fundraisers seem to be afraid of Darwinism. As it’s a pet subject of mine, I’ve spoken to many people about this over the seven years I’ve been in this sector. Some people are totally dismissive, simply asserting that evolution has no relationship to how and why people give to charity.

Others familiarise themselves with a relatively basic grasp of evolutionary theory, which they then use to show to those with less or no understanding of Darwinism how altruism is impossible if left to the devices of natural selection – this often involves a gross misunderstanding of the selfish gene idea. Yet there is simply reems of research and theorising, dating back 40 years and more, about how altruism could have, and probably did, evolve.

Some people even seem desperate that evolution should not have had a role in shaping our philanthropic tendencies. For them, showing that people are philanthropic partly because it is in our nature to be so would destroy some of the mystery and magic – it would unweave the philanthropic rainbow. I remember discussing these ideas with one fundraiser a few years ago. “But surely there must be more to charity than that,” she implored as my ideas began to make sense to her.

Of course, there is more to charity than “that”. Just because you can plausibly argue that evolution has shaped our philanthropic behaviour, that doesn’t negate our existing ways of understanding charitable motivations. Rather, it gives them a deeper explanation and context.

Three paradigms about giving

The are three broad ‘paradigms’ in thinking about why people give to charity.

One is that philanthropy comes from a sense of social or religious duty, which was the paradigm that drove philanthropy during the 19th and early to middle 20th centuries. Another is our current paradigm that says that people give because they are moved by and respond to a need – or a wrong – in the world. This is at the heart of modern professional fundraising.

This paradigm is shifting however. Theorists such as Alan Clayton, Kay Sprinkel Grace and Tony Elischer (to name just three, but there are more) are talking more about how giving fulfils a need in the donor and that successful charities will be those that can help them fulfil that need. This is not a Darwinian paradigm, but it does open the doors to Darwinian interpretations.

Fundraising is way, way behind the times in distancing itself from Darwinism and more than a year ago I lamented in this blog how this meant that fundraisers were missing out a wealth of understanding about what makes people’s charitable instincts tick.

I’ll not rehearse those arguments again, but please take a fresh look at that post. I’d also recommend that anyone who doubts that evolutionary theory has any relevance to charitable giving gets themselves copies of Matt Ridley’s The Origins of Virtue; and a great little book that’s part of the LSE’s Darwinism Today series called A Darwinian Left, by Australian moral philosopher and animal rights theorist Peter Singer.

This latest research by Oxford’s Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology is a perfect example of how an evolutionary perspective on charitable behaviour can help inform and refine fundraising techniques.

Why would you want to ignore it?

- Darwin £10 note enters extinction on 1 March (12 February 2018)

- How to use sex to improve your fundraising (18 June 2009)

- Were we born to give? We won’t find out just yet (5 July 2007)

- £50,000 in Darwinian matched giving on the Big Give Monday (20 February 2009)