Stop listening to your supporters

They’re just trying to rationalise. (Tell you rational-lies!)

Fundraising consultant Bernard Ross gets serious in part two of this #BlogOff, fighting the ‘no’ corner in the battle of whether you should listen to your supporters – or not. Read the opposing view from Dana Segal here.

Fundraisers are an emotional bunch. They care a lot about the bad stuff that’s happening in the world. And they desperately want everyone to care about it as much as they do. And they’re sensitive. So they spend a lot of time and effort listening to donors and supporters.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, this leads them to think the way to understand donors is to listen to them. My thesis here is that if you listen too much to donors you/ll be at best disappointed, and at worst very distracted. Instead you need to study what they actually do.

What follows is five reasons why you shouldn’t listen, drawn from my new book with Omar Mahmoud on how behavioural economics should change fundraising.

Reason 1: Donors… don’t know what they want

Famously, and perhaps apocryphally, Henry Ford said “If I had asked people what they had wanted they would have said a faster horse.” Apocryphal or not, there’s a strong element of truth in that statement. Yet we persist in using focus groups, online surveys and other forms of contemporary astrology to try and find out what donors or supporters think they want. The reality is that most donors, like most customers, prefer to operate within the bounds of what they know and would like to see that improved. For example, essentially the same thing made cheaper, better, or easier to use. We are profoundly creatures of habit. It avoids having to use brains or energy to make difficult choices.

The worrying implication is that donors will often support a campaign when asked about it because it seems like something they should want to do.

UK readers will remember Oxfam’s ‘positive’ Lift Me Up TV campaign.

The campaign featured positive images of how the lives of people in developing nations were improving thanks the work of Oxfam. The ad agency loved it, the Oxfam staff loved it, and the general public in focus groups loved it. “At last there’s a campaign which celebrates the success of development work and shows empowered people taking control of their lives.” Sadly, the campaign proved a real failure in terms of fundraising. And reinforces an unhappy truth that the kind of positive messages that people say they want to see, don’t, in general, actually drive successful fundraising.

(Sadly, it’s the messages of risk and threat of harm that most often do succeed. And we have a name for this in behavioural economics: the loss aversion heuristic.)

Let me be clear. Every socially concerned part of me would love positive success images to drive success in fundraising. Every practical pragmatic part of me recognises that it’s hardly ever true. Don’t trust them when people say they want to hear the good news.

Reason 2: Donors… make decisions based on emotion not reason, but they don’t like to admit it

One of the key tenants of behavioural economics is that people like to believe that they make decisions and judgements based on System Two – our rational worldview – when in fact they mostly make decisions based on System One – our emotional worldview. (For more on this see Thinking Fast and Slow on Wikipedia).

The Rokia experiment provides a powerful insight to this. In an experiment for Save the Children two groups of similar potential donors were asked to support either a specific 7-year-old girl named Rokia who faced starvation in Zambia, or three million children facing starvation in the same country.

Here’s the exact text for the two appeals. Decide which would be more likely to elicit a gift from you – A or B?

A) Any money that you donate will go to Rokia, a seven year old girl who lives in Zambia in Africa. Rokia is desperately poor and faces a threat of severe hunger, even starvation. Her life will be changed for the better as a result of your financial gift.

With your support, and the support of other caring sponsors, Save the Children will work with Rokia’s family and other members of the community to help feed and educate her, and provide her with basic medical care.

B) Food shortages in Africa are affecting millions of children. In Zambia, severe rainfall deficits have resulted in a 42% drop in maize production from 2000. As a result, an estimated three million Zambians face hunger. Four million Angolans – one third of the population – have been forced to flee their homes.

More than 11 million people in Ethiopia need immediate food assistance. They need your help now and by donating to Save the Children you can help.

You probably answered A. That’s what most people did in a famous study by Deborah Small, marketing professor at Wharton. Professor Small found that if organisations want to raise money for a cause, it is more effective in donation terms to appeal to the individual heart – and focus on individuals like Rokia – than to the mass head, which might say ‘please help whichever person or persons is most in need.’

Perhaps more distressingly for those of us who are keen to win over hearts and minds, the study also found that if a fundraising appeal highlighted Rokia and then included data about overall mass need in the country, donors actually gave less than they did when the data was left out. (You may want to read that sentence again. It has some profound implications for anyone trying to change minds and behaviour.)

Sorry. Donors like to say they are both rational and emotional. The truth is that in philanthropic terms emotion wins every time.

Reason 3: Donors… (and fundraisers) are overconfident

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias which encourages people to have a false sense of their own ability or contribution to something. It was first detailed in 1999 by David Dunning and Justin Kruger of Cornell University. The effect works in two ways. First, people mistakenly assess their ability or contribution as much higher than it really is – literally they think they are capable of things they are not. (If you’ve ever watched the auditions for the X Factor you can see plenty of evidence for this.)

Fundraisers tend to overvalue their own view about what works. And donors tend to reinforce this by overvaluing the importance of their opinion. (Think: how many of the director’s ‘great’ ideas were tested in focus groups and came back with a 5-star rating…and then failed?)

Second, and perhaps more important in this context, donors overestimate how philanthropic they are. The CAF annual fundraising survey of giving is useful and put together with good intent. But very often there is a conflict between the total amount of money donors say they give and the actual income of charities.

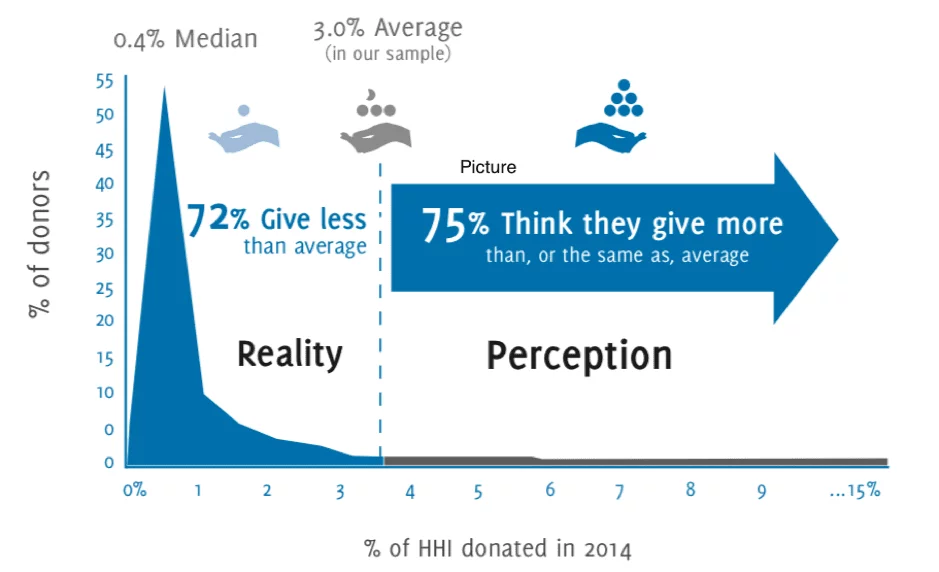

The chart below, based on US data, says the same thing but quantifies it. 75% of donors think they give more than the average, when actually 72% give less.

Sorry again. If we listen to donors and don’t study the data we can simply fuel their philanthropic fantasy.

Reason 4: Donors… don’t realise context (not commitment) is the key to most of their behaviour

A classic trap that fundraisers fall into is to try and help supporters choose how to help by offering them a range of choices about how to help and explaining clearly what the impact of their choice is. Donors say they want this. But in fact a lot of the evidence suggests that context not rational choice is a more important driver of success.

A key element in context is social proof – so who else is doing the same. Let’s illustrate this with a famous experiment originally run by Robert Cialdini, respected Professor of Psychology at Arizona State University.

He persuaded a major US hotel chain to trial different messages in hotel rooms to see which would have the most powerful effect getting hotel users to reuse their towels. This would help save the planet and, coincidently reduce the hotel’s laundry and room cleaning costs.

There were three versions of the message trialled:

Message 1: focused, as do many of these appeals, on the environmental benefits of reuse. If you’ve ever stayed in a hotel I’m sure you’ll have seen this version. In this case 35% of guests opted to re-use their towels. This was used as a the ‘control’ – or baseline – for the experiment.

Message 2: focused on social proof. This missed out the environmental message and stated, ‘most people in this hotel re-use their towels.’ In this case 44% of guests reused their towels. That’s almost 10% more people.

Message 3: here the researchers tested variations of the social proof message over several weeks. They tried to target it even more to ‘people like you.’ They adapted specific messages by mentioning gender ‘women/men’, ‘citizens’, ‘environmentally concerned individuals’, ‘guests in this hotel’ or finally, ‘people who stayed in this room.’ There were five variants in total.

Which message had the greatest impact in changing behaviour? Most fundraisers think the answer is one containing some sense of social identity – often they choose ‘gender’ or ‘citizen.’ In fact, the most effective message was the one saying ‘most people who stay in this room reuse their towels.’ That produced a 49.3% reuse rate – 15% more than the original environmental message. It’s not about the cause, it’s the social proof context.

The reality is more people tend to support you more as it becomes socially acceptable. Just because others do. Not for the cause committed reason they tell you. (Look again at the success of ice bucket challenge – what cause was it for again?)

Reason 5: Donors… mostly look for confirmation of their current views, and they don’t look very far…

We tend to seek out data that supports out our current beliefs. In behavioural economics it’s called confirmation bias. So it’s a challenge for me to hear Trump supporters claiming that the latest Twitter output from the White House is evidence of commitment to his declared policies. I hear exactly the same data as evidence of his childish ill-considered mood swings.

(I’m writing that sentence, of course, fairly confident that you, my target audience, share the same views that whatever Trump says will be nonsense. We share a confirmation bias about Trump.)

Donors also don’t look very far for data. Our lazy brains tend to focus on the ‘salience’ of data – information can we get that’s vivid, recent, negative, and extreme. It’s this kind of information that makes us worry about shark attacks when we’re on holiday somewhere tropical, when there are more deaths from falling coconuts in hot climates each year than there are from shark attacks.

Let’s take a fundraising example. Not all disasters receive equal media attention: the coverage of an event is often a function of its drama rather than its magnitude. A sudden catastrophe that kills hundreds in seconds will generate more coverage than an ongoing famine that kills thousands every day. It’s important for fundraisers to check not only the media coverage, but their target audiences’ awareness of such coverage.

Around 11,500 people died in the Ebola outbreak of 2014. That’s terrible – but a tiny number compared to the numbers dying in Yemen or Syria. But the income received by agencies like Médecins Sans Frontièrs for Ebola was far in excess of the relative funds given for these greater, less dramatic tragedies.

Why? Because donors see these types of events as more salient – and they confirm our, largely unfounded, view that the world becoming a more dangerous place. We can also see that the recent fall in donor confidence in charities is based on a very small, if nonetheless series of failing by a small number of charities.

Donors just don’t put the effort in to work out what’s really important. And it’s hard for us to counter the general media background.

Let me say it again even though you probably hear it as heresy. Don’t listen to what donors say – watch what they do and focus on that.

Change for Good – using behavioural economics for a better world by Bernard Ross and Omar Mahmoud can be ordered via Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.