Fundraising regulation needs to be better than this

Rogare’s director Ian MacQuillin asks what Lord Grade’s recent interview in the Daily Telegraph tells us about the direction fundraising regulation is taking.

Fundraising received one of its regular pummellings this past weekend when the Daily Telegraph* reported that the Fundraising Regulator was considering banning enclosures such as free pens and address labels in charity direct mail.

The source of this claim was an interview with the Fundraising Regulator Lord Grade.

However, we were all subsequently relieved to learn that lead claim in the article was actually not true, when F-Reg issues a statement to “clarify comments reported”, which it has been said were ‘taken out of context’. (Whatever the context, and whatever Lord Grade said, it did lead a highly experienced journalist to write of the putative ban on enclosures that “the threat has come from Lord Grade of Yarmouth”.)

However, it is reassuring to know that F-Reg has no plans to “ban” such enclosures, though it is now reportedly asking charities to “review” their use of them. Writing in Civil Society Voices, Lord Grade says:

“We will discuss with charities how they justify their decisions to send such gifts and answer questions from the public as to why funds are being spent like this, since our Complaints Report highlighted it as an area of concern.”

F-Reg’s first complaints report – published last month – revealed that of around 16,000 complaints about direct mail, more than 80 per cent related to enclosures.

In the Telegraph interview – presumably the bit that is not taken out of context – Lord Grade says that at first ader couldn’t understand why people would be complaining about a free gift. But he continues:

Advertisement

“They are saying ‘why are the spending this money, which could go to charity’ – which is actually a really smart response. So we are learning from the public.”

Because of this, Lord Grade says he now agrees with the public’s concern about enclosures, hence F-Reg’s intention to ask charities to review and “justify” their use of – and cost of – enclosures. And while F-Reg does not intend to “ban” enclosures, we can assume that these reviews will not be done simply of the sake of it, and some action might ensue in the future.

So the bases for F-Reg asking charities to review their use of enclosures are:

- They are a public concern because lots of people have complained about them

- F-Reg has “learned” form the public that the money spent on enclosures “could go to the charity instead”.

This begs a rather humungous question:

- That because something is a “concern” to the public, something should be done about it.

And raises a further question about the competence of F-Reg:

- How robust are the complaints stats on which F-Reg is basing this?

How relevant is the public’s ‘concern’ about enclosures

Just because the public have a concern about any particular issue, it does not follow that something ought to be done to redress those concerns. For sure, it should highlight concerns among the sector that something might need to be done to address those public concerns, but not necessarily redress them.

To decide what might need to be done as a matter of redress would require consideration of many other factors over and above simply whether they are a ‘concern’ to the general public.

For example, we need to know the nature of those complaints. If they are of the type that people were sent enclosures when they specifically asked not to receive them, or they were the type of enclosures that are prohibited under the code (the type intended to induce financial guilt – s6.3b), then there is a prima facie case for F-Reg action in those specific cases.

However, if the nature of the complaints is simply that people don’t like receiving them, the case for F-Reg intervention is less clear-cut. F-Reg sees itself as a consumer protection champion – a position it has stated on many occasions – so it might think that it is beholden to act in such circumstances. However, enclosures are used by charities because they work, and Lord Grade betrays his ignorance – yet again! – but saying that he and his organisation have learned from the public that the money spent on free gifts could “go to the charity instead”.

How reliable is F-Reg’s evidence about enclosures?

But let’s assume that F-Reg is right to act on public concern and it is basing this on the evidence for that concern as revealed in its complaint report. How robust and reliable is that evidence? That’s open to question, because there is a discrepancy between F-Reg’s figures and equivalent figures complied by the Fundraising Standards Board in every one of its annual complaints reports.

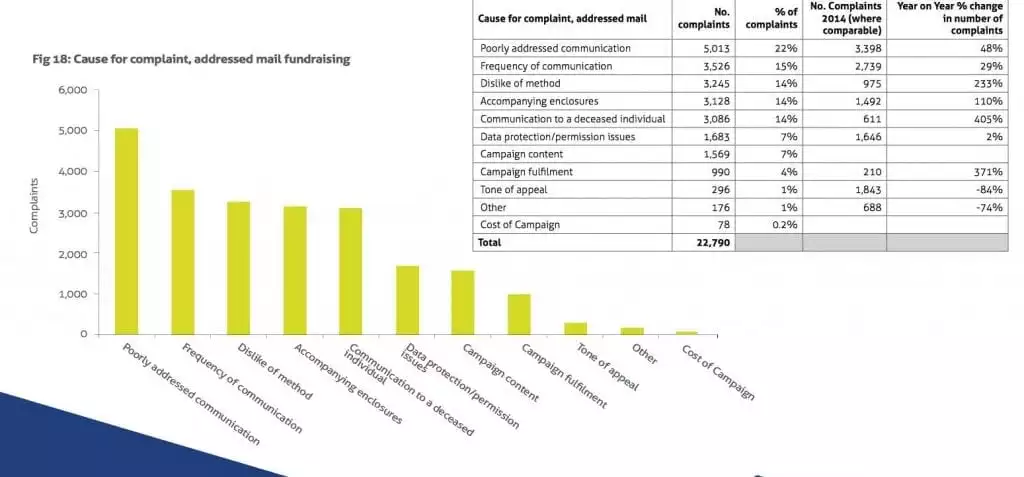

According to F-Reg, 82 per cent of complaints about direct mail were about enclosures.

However, the 2016 FRSB complaints report puts this figure at 14 per cent (see image).

By contrast, the FRSB regularly reported that the most common type of complaint (22 per cent) about DM related to “poorly addressed communications”. Yet according to F-Reg, complaints about similar levels of poor data accuracy now account for just 0.55 per cent.

Something is clearly not right here. I can think of only three explanations.

- There as been a marked change in behaviour in what people complain about since F-Reg took over the reins from FRSB

- F-Reg stats are wrong

- FRSB stats are wrong.

If I were forced to bet my mortgage on this, I know which one I’d put it on (though admittedly, they could both be wrong).

If F-Reg is wrong about the level of public concern about enclosures, then it has no basis or authority for stating that there is such concern, much less pontificating in the national media that it is going to take action about it – even if this is merely to ask charities to “review” their use of these things.

In the interests of transparency and accountability, it seems pertinent to put two questions to the Fundraising Regulator:

- How confident are you in your complaints statistics?

- How do you account for the discrepancy between your figures and the FRSB’s?

‘Learning’ from the public

F-Reg’s readiness to listen to the public, to “learn” from them, and then act on what it has learned – however ill-informed that lesson may be (such as money spent on fundraising could “go to the charity instead”) – highlights what I think is a worrying direction that F-Reg is taking in its regulatory ethos.

This was to the fore in the recently-published research that accompanied F-Reg’s review of the code of practice earlier this year.

The code of practice (s1.2f) prohibits fundraisers placing “undue pressure” on people to donate.

I had assumed that the way F-Reg would regulate breaches of this prescription would be by precedent, taking a ‘man on the Clapham omnibus’ approach to deciding whether – in the case of any particular complaint – ‘undue’ pressure had been applied. The result of that decision would then become part of fundraising’s ‘canon’ law, and we would thus gradually build up a picture of what was and was not ‘undue’ pressure based on what people actually complained about.

That however doesn’t seem to be the way F-Reg is going about it.

Undue pressure

A number of focus groups were conducted for F-Reg’s recent research, some of which considered the question of “undue pressure”, finding that the public considered that “undue pressure was deemed to have been applied” when a fundraiser sought to:

- Prompt the potential donor with a high suggested donation and not appropriately adjust the amount during the conversation

- Referenced the potential donor’s personal life in order to provoke feelings of guilt

- Refuse to actively listen to and observe the information provided by the potential donor during the exchange

- Induce a sense of overt urgency in the interaction

- Adopt an aggressive or overly sales-led style.

The research report says:

“The public unanimously rejected any attempt by the fundraiser to induce feelings of guilt by contextualizing a monetary donation with reference to their private lives, for example insisting that a donation would only mean buying one less take away or suggesting that if the member of the public could afford to buy a coffee they could afford to make a donation to charity.”

What they’re talking about he is ‘for the price of a cup of coffee…’ lifestyle comparison appeal – which academic research shows encourages more donations.

So having discovered what the public consider to be ‘undue’ pressure, what does F-Reg intend to do with this information?

The question we ought to consider – and indeed ought to worry us – is whether F-Reg intends to amend to code of practice to prevent fundraisers from doing anything that their research tells them causes ‘undue’ pressure, such as banning lifestyle comparison appeals.

Underlying ethos

The underlying regulatory ethos that both this report and Lord Grade’s interview with the Telegraph point to is one whereby F-Reg “learns” from the public what they don’t like, and then takes action to protect the public from such actions.

F-Reg justifies this first by repeatedly claiming that its role is to act it the interest of the donor, and then by making the philosophically-flawed argument that ‘what’s in the best interest of the donor is necessarily in the best interest of the beneficiary’. Just one example shows this does not follow. Since hardly anyone actually likes street fundraisers (most people appear neutral with a significant vehemently-vocal minority who really dislike them), the general public utility could be raised by banning ‘chuggers’ entirely: no-one would miss them and a fair few would be delighted to see the back of them.

It’s not so easy to argue that the resultant diminished pool of donors and income thus lost really is in the best interest of beneficiaries, unless you pile on a lot of auxiliary assumptions such that ‘removing chuggers really is in the best interest of the beneficiary because the long-term increase in public trust will offset the short-term loss of income’ – claims that need a lot of careful evidence to support them, and can’t simply be asserted as somehow ‘self-evident’.

Acting to ameliorate any public concern about fundraising – whether lifestyle comparison appeals, street fundraisers, or enclosures (whatever the nature of that ‘concern’ actually is) – must be balanced against the potential harm that could do to the funding of beneficiary services. This is the foundation upon which Rogare’s normative theory of fundraising ethics is built, and something we have argued ought to be adopted by those regulating fundraising.

Yet this is something that F-Reg assumes it has addressed through its claim that acting in donors’ interest means it is also acting in beneficiaries’ interests.

So while F-Reg has categorically stated that it has no (current) intention to ban enclosures in direct mail, and the reporting of this in the Telegraph was due to a misunderstanding or being taken out of context, we should be very concerned that the chair of the Fundraising Regulator was even saying anything that could be misinterpreted this way.

And so that brings us to Lord Grade.

Fundraising’s Boris Johnson

Earlier this year I wrote on blog on UK Fundraising calling for Lord Grade to resign as chair of the Fundraising Regulator. Nothing that has happened since then has given me cause to revise that opinion, while his performance in the Daily Telegraph last Saturday leads me to think calls for his resignation need to be reignited.

Lord Grade has form in giving misleading information to the media (even accepting that on this occasion, what he said to the media was accurate and was ‘misinterpreted’ by the Telegraph’s chief political correspondent): more than once I’ve heard him talk on Radio 4 about the Fundraising Preference Service and get fundamental details wrong.

However you look at this, Lord Grade seems more and more like fundraising’s Boris Johnson.

This summer, IoF chair Amanda Bringans met Lord Grade, who, she says in this Institute of Fundraising blog, agreed to her request for more positive messages to support fundraising.

In the short Telegraph interview, Lord Grade:

- Implies use of the FPS is mainly by people wanting to protect elderly relatives or friends

…though F-Reg has released few figures on the usage of the FPS. - Restates his position that he pretends to be a barrister to intimidate fundraisers who contact him

…which at the very least calls into question his impartiality in regulating those same fundraisers, irrespective of any other ethical considerations - Says charities that have not paid the levy or responded to comms about it are acting “unprofessionally” and think they are “above” regulation

…ignoring the possibility they might have serious concerns about the quality of regulation they are being told to sign up to. - Says he is concerned about lack of awareness of the fees charged by crowdfunding platforms – JustGiving is the only one named in the article – though he says it is not up to F-Reg to tell anyone how to run their business.

Is this the kind of positive messaging about fundraising that IoF had been hoping for?

Better than this

About this time last year, I met Stephen Dunmore at F-Reg’s offices. The meeting had been precipitated by a blog I’d written on Third Sector that had been critical of the way F-Reg had implement the results of its consultation on the FPS.

The first thing Stephen said to me was: “Do you think fundraising needs to be regulated?”

I replied that of course it needs to be regulated.

Fundraising needed to be regulated then, it needs to be regulated now, and it will need to be regulated in the future.

Just better than this.

- NB The petition calling on Lord Grade to resign that someone up after my original blog came out is still open.

* The online version has now changed its headline from:

‘I’m going to put a stop to those free charity pens’

To:

‘I know how to stop charities making cold calls’