What can charities learn from the 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer?

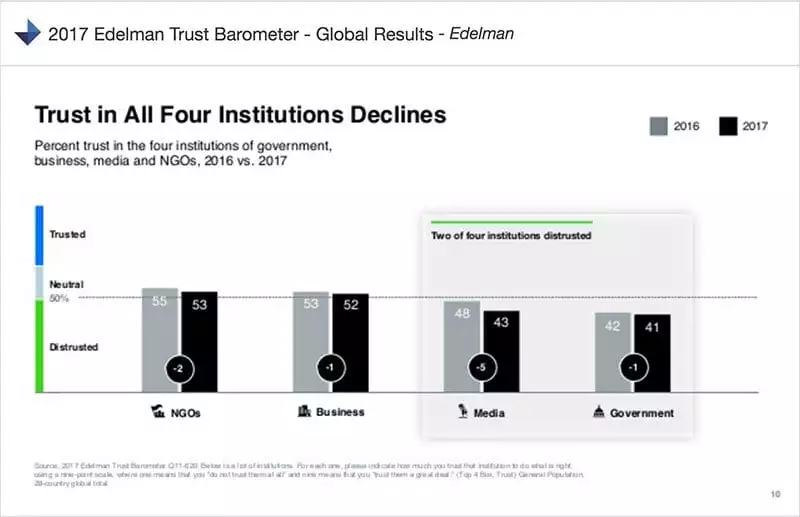

Research firm Edelman’s 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer, published yesterday, presents a bleak picture of declining public trust in four key pillars of society – NGOs/charities, business, government and media. What can charities learn from this depiction of current society?

The 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer is the firm’s 17th annual survey of institutions’ trust and credibility in the eyes of the public. The survey was carried out by Edelman Intelligence and consisted of 25-minute online interviews conducted from 13 October to 16 November 2016.

The global survey includes data specific to the UK, and a supplementary research project carried out between 23 December and 9 January.

Global findings

Edelman report that:

“Trust in business (52%) dropped in 18 countries, while NGOs (53%) saw drop-offs as high as 10 points across 21 countries.”

It describes this as

Advertisement

“the largest-ever drop in trust across the institutions of government, business, media and NGOs. Trust in media (43 percent) fell precipitously and is at all-time lows in 17 countries, while trust levels in government (41 percent) dropped in 14 markets and is the least trusted institution in half of the 28 countries surveyed.”

NGOs might be the most trusted of the four sectors, but there is scant reason for satisfaction, as they rank only in the ‘neutral’ level, and within that dropped two per cent in the year, closer to the ‘distrusted’ section. They remain the most trusted of the four sectors analysed, but by a tiny margin.

Prime focus on business

The report and Edelman staff’s comments on its findings focus a great deal on the importance of business, and not NGOs.

Kathryn Beiser, global chair of Edelman’s Corporate practice, argues:

“Business is the last retaining wall for trust. Its leaders must step up on the issues that matter for society. It has done a masterful job of illustrating the benefits of innovation but has done little to discuss the impact those advances will have on people’s jobs.”

Of the four sectors, there is less coverage and discussion on attitudes towards NGOs and charities, which is why some analysis of what might be learned by the charity sector could prove useful.

Trust in the UK

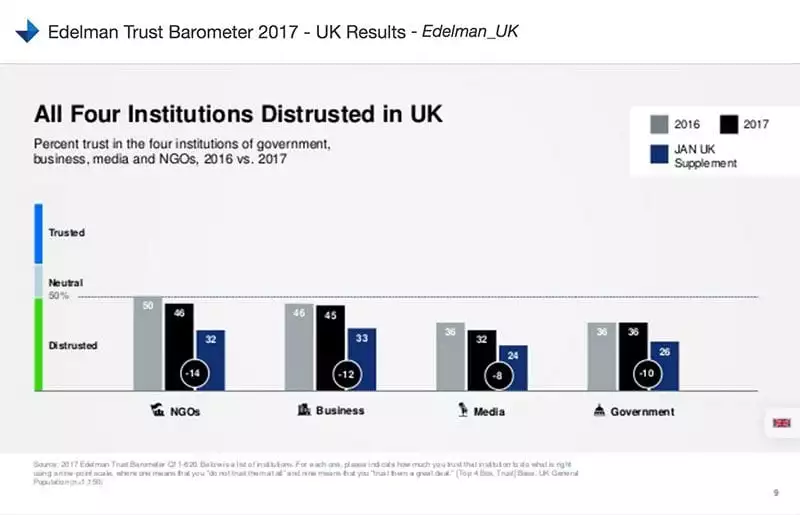

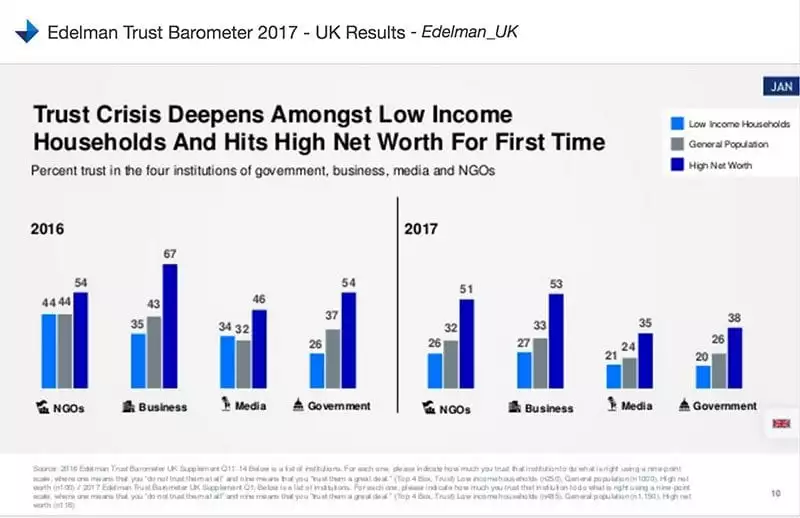

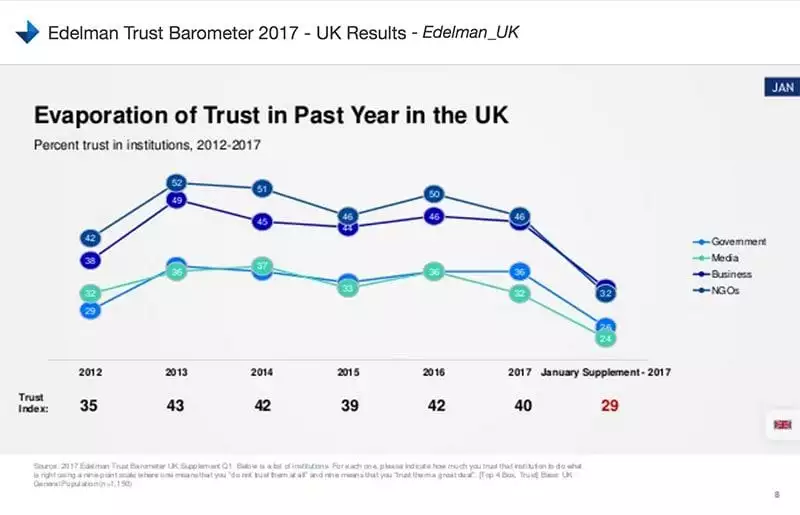

The UK figures for NGOs are worse than the global averages, with a starting point of 50% in 2016, dropping to 46% (and into the distrusted category) in 2017. Worse, the level of trust has dropped to 32% from the end of 2016 research to that of January 2017!

For the past five years, NGOs were the most trusted of the four institutions in the UK, but as of January 2017 they have slipped into second place, just behind business.

In the UK NGOs are now trusted a little less than businesses.

All sectors of course have suffered a reduction in trust in the past year in the UK, but it is alarming that charities should suffer the same fate, not least given the scale and diversity of the sector.

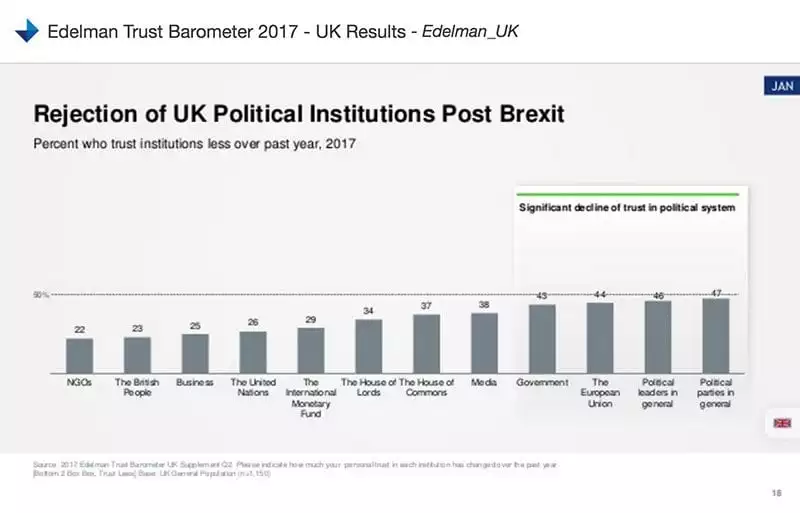

That said, if you are looking for signs of comfort, NGOs are the “least rejected” of the political institutions following the EU referendum. Hardly an endorsement of the sector, but it arguably makes a reversal easier than, for example, political leaders and political parties.

At least NGOs in the UK have experienced the least decline of trust amongst political institutions…

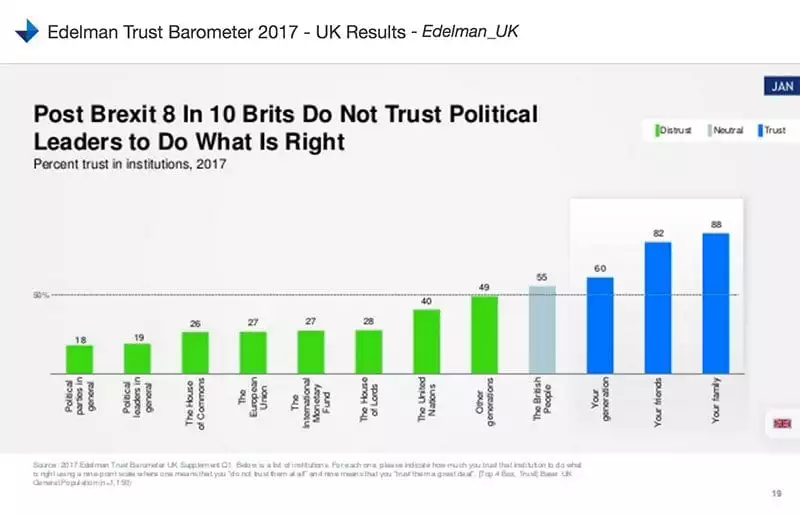

Edelman claims that theirs “is the first comprehensive data to track the rise of populism in post-Brexit-referendum Britain”.

Trust in politicians is down. For example, trust in Boris Johnson has fallen from 37% to 24% within a year. Prime Minister Theresa May, at 35%, is the most trusted politician, although David Cameron was on 40% this time a year ago.

Trust in British CEOs (of ‘businesses’, so presumably not including not-for-profit organisations like NGOs) has dropped by 12 points in a year to 28%. Edelman suggests that collectively their reputation has been “battered by discontent over excessive pay, corporate malfeasance over tax and accounting, and the sense that they are managers not leaders”.

Solutions?

Is there a solution? In the video summary above, Richard Edelman proposes:

“Institutions have to get outside of their classic box. Business as actor and innovator, government as regulator and referee, media as watchdog and NGO as social conscience.

“Each of these institutions actually has to move together, to help the consumer and voter understand the true consequences and implications automation and globalisation”.

Lessons for NGOs and charities?

The UK findings highlight some challenges but also some opportunities for charities to try to regain public trust. Some of these tactics will already be familiar.

Jim Bowes, CEO and co-founder of Manifesto, an agency which works with many social good organisations, commented:

“Charities must focus on how they communicate with their target audiences, this will mean revisiting their core purpose and re-evaluating who their audience is and what motivates them. Too often charities try to appeal to everyone without speaking to anyone in particular; being too grand can lead to confusion and mistrust. Charities need to own a subject, speak from the heart and tell their real story.

“This will by no means be an overnight job. It needs a well thought out communication strategy that speaks to the audience on the channels they use, in a plain and honest way – only this, and respecting people’s data, will help charities regain the trust of the UK public.”

So, what can charities learn and do about this trend?

1. Build your social capital

Whom do UK citizens trust most? Their family and friends, and people of their generation.

The (global) report states:

“There is evidence of even further dispersion of authority. A person like yourself (60 percent) is now just as credible a source of information about a company as is a technical (60 percent) or academic (60 percent) expert, and far more credible than a CEO (37 percent) and government official (29 percent).”

What can charities do about this? Focus more on building up their social capital, inspiring and enabling individuals to tell their contacts how good their experience with a charity has been, and how they are committed to helping the charity. Digital channels should focus in this area, but so too should community events and an opportunity to meet with individuals. First-hand experiences of charities and the opportunities to share these experiences could become even more important.

Will story-telling rescue the charity sector’s reputation? On it’s own, of course not. But if you see how some charities report the life-changing achievements they make, you will know how much better many charities could do.

2. Don’t assume major donors are immune

For the first time the Edelman Trust barometer has noted that the drop in trust in political institutions is affecting wealthier people in the UK.

In 2016 54% of High Net Worth individuals trusted NGOs, but by January 2017 that had dropped to 51%.

While there is no correlation between the high net worth individuals who took part in the survey and any charitable giving they undertook, it is worth being aware that major donors might require even greater assurance from charities, or demand a greater involvement in the charity.

3. Who speaks matters

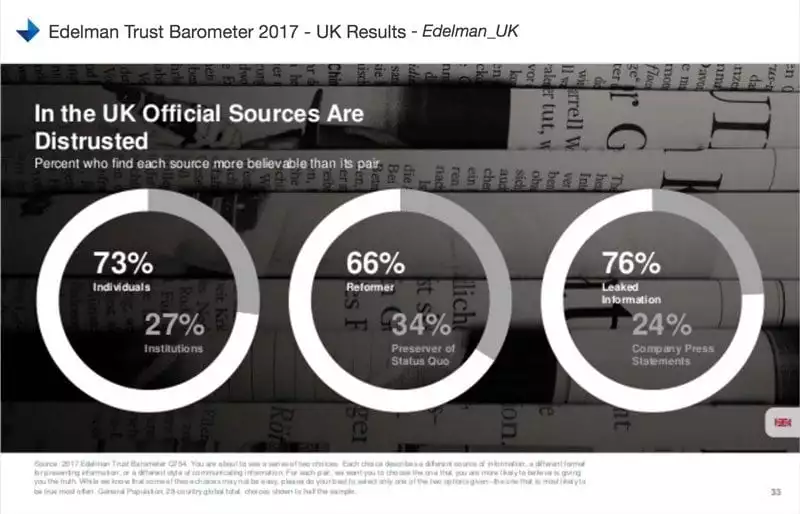

The Edelman report suggests that many people distrust official sources as their source of news or information. There is a preference for leaked information over company press statements, for example.

The preference for individuals over institutions as trusted sources of information relates to the earlier suggestion that charities should continue to inspire their supporters and beneficiaries to tell the story of their success.

The public’s attitude to reformers vs preserver of the status quo is a particular challenge to the charity sector as a whole. Some charities are explicitly aiming to maintain a status quo e.g. of preserving access to heritage, environment, learning, equal rights, healthcare and other benefits. Others on the other hand were set up to bring change.

If change is what the UK public is desperate to see, or at least hear about, then many charities should be in an excellent position to appeal to them. Presenting what they are doing and achieving in terms of reform, and not delivering that information in the style of a “company press statement” is one more way in which they might overturn this drop in trust.

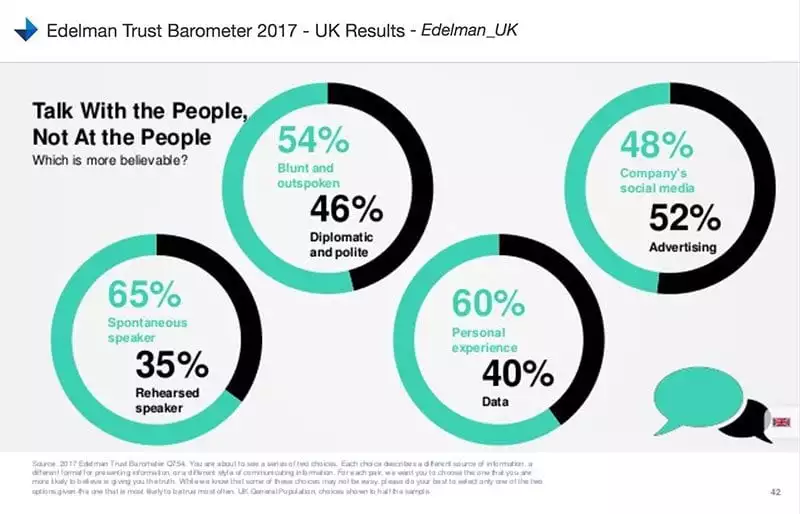

4. Talk with the people, not at the people

This recommendation is part of the Edelman’s report. Personal experience, spontaneity rather than rehearsed speech, and outspoken approaches are trusted more in the UK, it seems.

Many charities have rightly got very professional in terms of their public and media speaking and presentation skills, training staff and volunteers to respond well to journalists.

Perhaps things have moved on and many people see such polish as less convincing.

Yet many charities and campaigning NGOs in particular were only created because a small group of people were prepared to be blunt and outspoken about the problem that they set about tackling. Even now, many of the problems they tackle in the UK and around the world are arguably worthy of blunt and outspoken language.

Of course, diplomatic and polite language have an essential role in public communications. But perhaps a less polished, more spontaneous response would resonate better with the wider public.

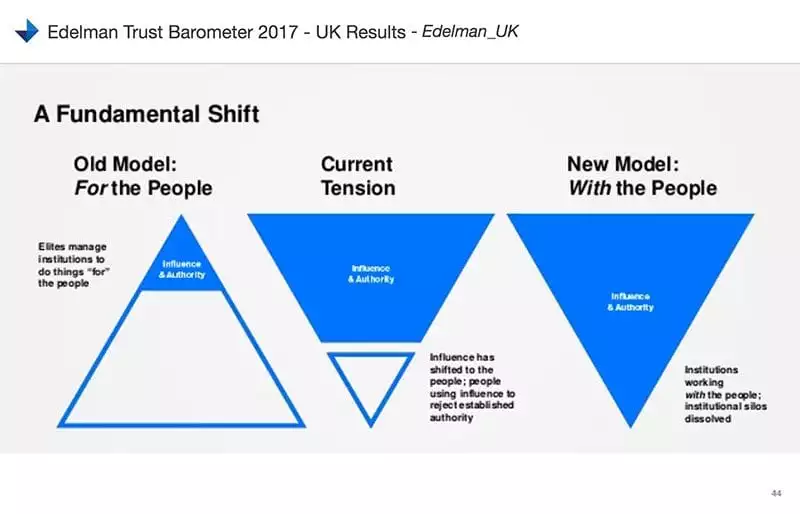

5. With the people

Again, Edelman suggest a route for all institutions to try to restore trust. They suggest, in broad terms, moving from organisations that claimed that they were an authority and were doing good “for the people” to organisations that acted and demonstrated that they were doing good by working “with the people”.

Some describe this approach as “movement building”.

Again, a participative approach and the dissolution of institutional silos are not new suggestions for the charity sector. Indeed, you can see some of these changes underway in the form of the success of crowdfunding platforms and of campaigning platforms like Avaaz and 38 Degrees.

Ongoing issues about trust

The issues of public trust and indeed the genuine levels of trust are debated, and there are plenty of issues that the charity sector faces an ongoing struggle in presenting convincingly to some media outlets and politicians, not least the importance of (effective) fundraising expenditure being seen as investment rather than simple costs, of the idea of charity expenditure as ‘overheads’, and of the need to pay decent salaries to charity staff and leaders in particular.

But the findings of the Edelman report suggest that the fundamental questions about how a NGO/charity is structured, how it is run, how it reports its impact and who does so, and how collaboratively it works are becoming ever more urgent issues to address.

Read more:

- Trust in charities at highest levels since 2013, says nfpSynergy

- Charity chief executives more trusted than politicians, but less than hairdressers