Who is thinking about the future of fundraising?

Howard Lake is, and here are my thoughts on his excellent white paper on the challenge and possible directions from which progress might appear. Please read it.

Ever since Howard and I talked over dinner at the IoF Convention in 2018, I have been waiting for this. I’m not sure why I don’t know that others are thinking at this level. There is a lot of talk about, for instance, behavioural science, and I find it fascinating, exciting and compelling, but essentially it is tactical not revolutionary.

What Howard is talking about is revolutionary thinking.

Advertisement

Before I start to comment on his paper, may I lay down a couple of my own givens?

First, I believe one thing on which I am unshakable. The natural instinct of individuals to want to make a difference to the world by giving money and time to help meet needs in the community, in society, or across the world, is the same now as it was 1,000 years ago. It was the same in 1389 during the re-building of Troyes Cathedral and will be the same in 1,000 years’ time – so long as the human race hasn’t been foolish enough to allow itself to become extinct.

What has and will change is the way that charities harness that desire to make the world a better place. This is pretty fundamental.

Secondly, the word ‘innovation’ always makes my hackles rise. When I was at NSPCC there was once a discussion at SMT about making ‘innovation’ a KPI. One of maybe just five or six. I vehemently argued against this. Why should innovation, per se, be something to be celebrated?

I hear fundraisers today saying that conventional fundraising is broken, and so innovation is critical to future success. Was the Ice Bucket Challenge the result of innovative thinking? Was the amount of time and money spent by charities trying to dream up their own innovative version of the Ice Bucket Challenge time and money well spent?

We don’t need afternoons with blank sheets of paper, flip charts and post-it notes.

We need thinking, analysis, ideas and rigour. As well as creativity and lateral thinking, of course.

To my mind, effective innovation starts with two things.

First, a thorough understanding of current best practice. How did it come to be so? What was fundraising was like 2,000 years ago, as recorded in the Bible? What was fundraising like 1,000 years’ ago, for the rebuilding of Troyes Cathedral? And just 50 years ago, when Harold Sumption articulated so many fundamental truths about fundraising?

And then, more recently, how has fundraising best practice changed in the time since you and your team started as fundraisers?

Secondly, looking outside our sector, and gather the learnings from other sectors.

Commerce and technology obviously. And also psychology, sociology, social psychology, political science and economics, to name a few.

With all of that insight, then to think. What can we learn? What insight can we draw? How might the learning of other sectors be brought to bear on fundraising?

How can we connect what is happening in one place to what is happening in another place, and come up with something previously unthought-of?

Then, and only then, to ask What if…?

That, for me, is what innovation should be about.

Howard Lake’s white paper

Coming to Howard’s paper, he says that only major donor income and legacies are increasing. I regard that as very significant.

Trust income will either come from trusts set up by major donors, or institutional trusts, whose giving will be determined by the performance of their investments.

However, I’d be very surprised if there hasn’t been a significant increase income from companies. Tell me if I’m wrong.

During the Full Stop Appeal NSPCC was at the leading edge of creating integrated company partnerships. There might be a promotion, sponsorship, employee fundraising, payroll giving and events. Directors would be cultivated as major donors. ‘Charity of the Year’ adoptions became commonplace. Then the rise in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the triple bottom line.

All of this being seen together as an integrated partnership between both the company and the charity. One that would evolve over time.

Has this not resulted in an increase in income?

If I’m right, then essentially that leaves Individual Giving. Lowish giving by individuals making gifts, setting up monthly direct debits, taking part in mass participation events or challenge events, or just buying a poppy on Poppy Day, and so helping to raise £50,000,000 on the one day.

So how do we measure success with individual givers? How are we innovating, according to my definition of ‘innovating’?

It is nearly ten years since I regularly attended review meetings between the charity and the agency. Or, rather, two agencies: below-the-line and above-the line. We would look at the relative performance of donor recruitment channels. Direct mail – door drops – DRTV – inserts – off-the-page – BRTV. And then face-to-face and door-to-door.

How much has changed?

When sending an Appeal to donors we might do a split test.

Spend on approach A and get 46% return, after, say, six months.

Spend the same on approach B and get 54% return.

So, approach B ‘works better’ than approach A, and should be used in future.

That’s the purpose of split tests, isn’t it?

But does it work better, if approach A gives the donor a better experience than approach B, and so increases the lifetime value? And approach B reduces it?

How much has changed?

In 1991 I had the pleasure of working with John Watson on the first successful DRTV ad, ‘Ellie’.

Over a couple of years John’s agency and the NSPCC team refined and honed it. It was then pretty much perfect, of its time. But 28 years later the DRTV ads I see are almost identical. Exactly the same format, the same length and the same ‘ask’. ‘£2 a month.’

How much has changed?

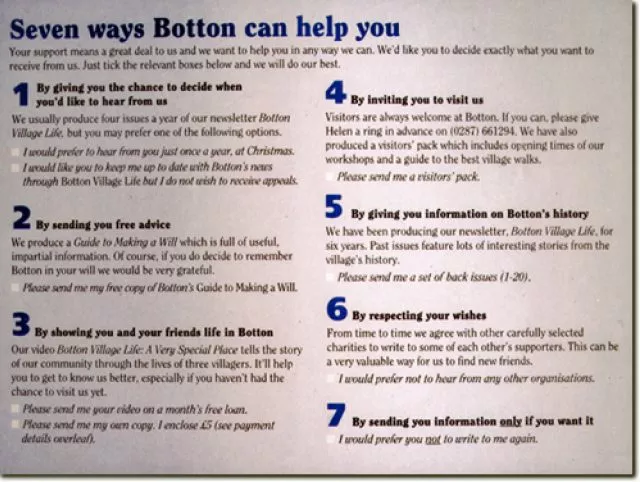

This example of giving donors choices in how the charity engages with them, created by Burnett Associates, is 30 years old. It is clunky and dated. But it is really significant.

How has the thinking behind it evolved? Show me an example that has benefited from 30 years of research, insight and learning? I suspect you can’t. Few charities have even reached this level of sophistication.

How much has changed?

Meanwhile, what is happening in the real world?

In 1994, Jeff Bezos founded Amazon. (Put your own views on employment practices etc. to one side. They are not relevant here.)

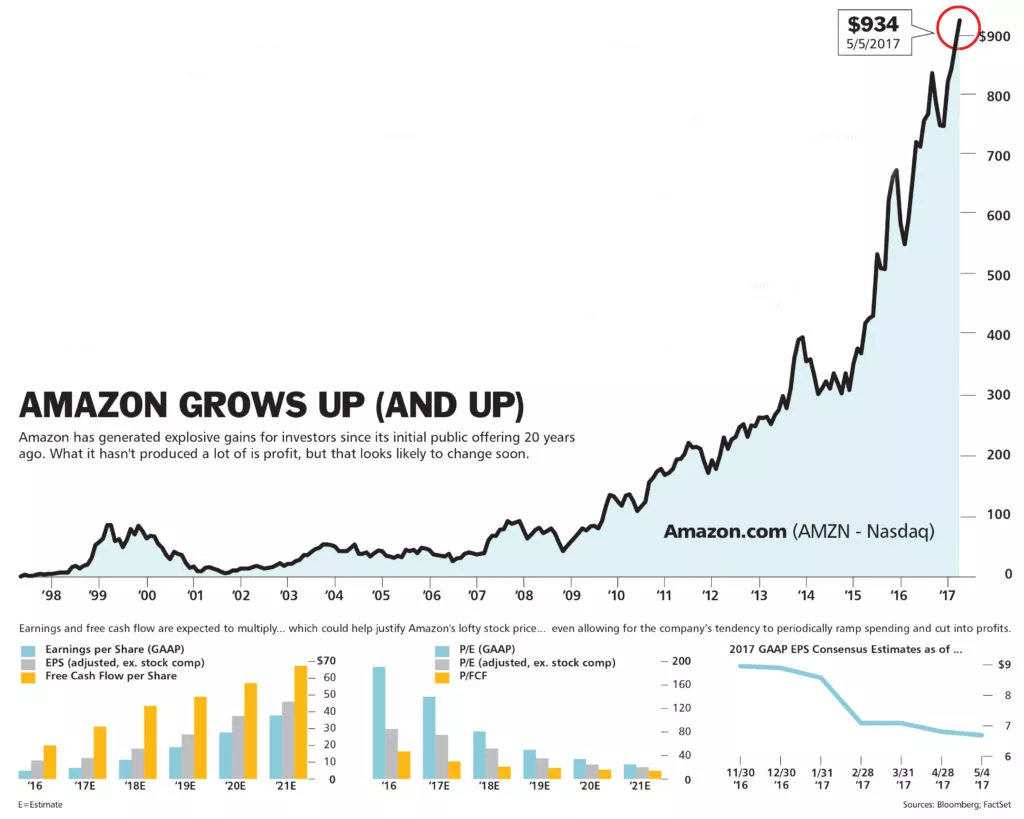

He sold books online. He insisted he was not in the book business but in the information business. Seven years later, in 2001, when I was aged 51, Amazon made its first profit. 17 years later, last year, Amazon’s profit was £3,000,000,000.

Artificial Intelligence has evolved in leaps and bounds since 1956, when I was six years’ old. We’re still only scratching the surface. I’m quite sure that, within a few decades, robots, or humanoids, will be able to do pretty much everything a human can do.

Surgery? Yes. They will have access to all the knowledge, wisdom and insight of all our surgeons across the globe.

Lawyers? Yes. They will have complete access to all case law.

Manual labour? Yes. They will know all the ‘tricks of the trade’, be stronger and more efficient.

Stephen Hawking was so aware of AI’s significance that he was concerned that the development of full Artificial Intelligence could spell the end of the human race. Of course, we must make sure that it doesn’t.

But that won’t mean that there won’t still be needs to be met, but we will have vastly more time to endeavour to meet those needs.

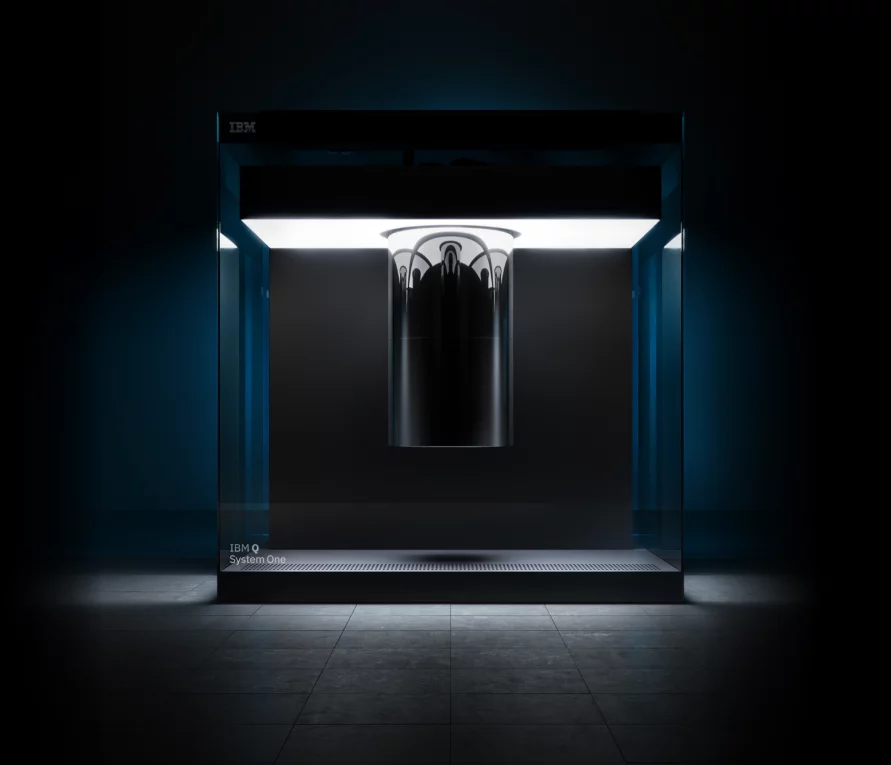

The IBM Q System One quantum computer. The temperature is kept just above absolute zero – colder than outer space. The casing also seals out the external universe of noise and interference.

I can just grasp the concepts behind quantum computing, which was only conceived in the early 80s, when I was in my 30s.

Even I know that ordinary computers store data and perform computations as a series of bits that are either 1 or 0. Quantum computers use qubits. Each qubit is somewhere between 1 and 0 but you don’t know where. The implications of this are vast.

By the time you had 280 perfect qubits, you would need every atom in the universe to store all the zeros and ones.

Quantum volume is doubling every year, according to IBM, but nobody can say how far this doubling might go. When the first computers were invented, their inventors had a good idea of what they could do.

No-one has the remotest idea of what quantum computers might be able to do.

So how has fundraising evolved whilst the world has been evolving so fast?

Howard writes that Blackbaud’s Steve MacLaughlin tweeted this year: “For over 40 years now, the share of wallet going to charitable giving has been stuck around two per cent.”

Isn’t this odd – surprising – even shocking?

Let me come back to Howard’s white paper. He writes:

“For example, online retail spending has increased to over £70 billion a year in the UK, and about a fifth of all retail spending now takes place online. A small percentage of that figure donated to charities through affiliate commission would make a huge difference, but this has not happened.”

Why?

Then he writes:

“Digital fundraising, the area where scale, automation and personalisation has the greatest potential, has shown great innovation and increasing sophistication. Yet its evolution is unevenly distributed amongst charities, many of whom still report a lack of access to digital skills.”

Why?

Howard’s paper suggests various possible ways of creating a quantum leap in fundraising.

He talks about a campaign to implement a Robin Hood Tax, a microdonation scheme that would consist of a tiny donation to be taken from each financial sector transaction.

Also affiliate shopping schemes which have the potential to divert a small slice of the population’s multi-billion pound online shopping expenditure to a charity of their choice. Topping-up or rounding-up donations to the nearest pound could enable millions of us to give small amounts almost daily.

Alternatively, Howard says, growth could come from a sector-wide reappraisal of whether charities are finding and recruiting the very best fundraisers, tackling the issues of lack of diversity and equality.

Then he talks about the potential of collaboration between charities, and a possible Incentive prize.

You really need to read Howard’s paper.

Let me posit one thought from me. Just one.

As a self-confessed technological disaster, I am the last person to suggest how we should harness technology massively to increase income, but I do have a view as to the what. What we should be trying to achieve. What we should be demanding of rapidly evolving technology.

That we should be able to regard all of our existing donors, our potential supporters, and the 50% of people in the country who are never even going to think of supporting us, as segments of one. Literally. We should know so much about people that we can use technology to treat each one of our donors as individuals, knowing:

• Why they support us?

• Why us, and not another charity?

• What made them start to support us?

• Which aspects of our work do they particularly like?

• And which they’re less interested in?

• What parts of our communications with them do they like?

• And which don’t they like, and so we should change?

• Whom do they know, to whom they might be advocates of our work. And how can we go through our donor to the prospect? (c.f. Richard Turner)

• And so much more. So very much more. How many variables? 00s? Why not?

Over the last few years I have been doing work with Salesforce.org. I have seen the power of their current technology. I suspect very few charities are using even one tenth of that available technology. And I’m pretty sure Salesforce.org haven’t yet reached one tenth of what they will develop over the next ten years.

So you should be anticipating that the degree of individualisation in your charity should be increasing 100 times over the next ten years. And maybe achieving 10 times results.

Howard reports that engineers at X (formerly Google X), the division of Google that focuses on producing major technological advances, operate with the notion of ‘10x thinking’. They describe this approach thus: ‘true innovation happens when you try to improve something by 10 times rather than by 10 per cent’.

Is that built into your thinking? Do you believe I’m totally wrong? And Howard? And Google X? Or are you so busy with the day job that you haven’t really given it much thought, at the level Howard suggests?

How many of you have embraced ‘disruptive innovation’?

“A disruptive innovation is an innovation that creates a new market and value network and eventually disrupts an existing market and value network, displacing established market-leading firms, products, and alliances.”

That’s what Jeff Bezos did. That’s what we must do.

(And this is no way inconsistent from my views on ‘innovation’, above.)

I can’t believe that in ten years’ time we’ll still be judging our success by the response rate on a cold direct mailing.

Thanks, Howard, for writing the article. I hope that others in the sector will read it, be inspired by it, or even consciously reject it. But it is too significant to the long-term future of fundraising just to ignore it: not to engage with your thinking.

Giles Pegram CBE

Consultant

1.xii.2019