Has this 50 year old piece of fundraising ever been bettered?

You may well have seen this ad before, because many experienced fundraisers, including me, believe it hasn’t. It has been analysed before, (see below) but I hope I can give a different perspective.

Ken Burnett once criticised me for being over-analytical. I took it as a great compliment. But if you don’t like minute analysis, stop reading now.

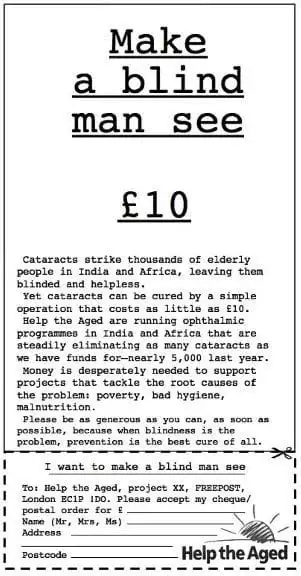

‘Make a blind man see. £10.’

Nearly half the total space. Just six words. Encapsulating the problem, the solution and engaging the potential donor with the possibility of doing something extraordinary. A total case statement.

Let’s just put the figures into perspective. In today’s money, this is asking for over £100. In a single cash gift. For just one person in need. Today, charities compete on price. A £3 text can help change the world. Is this madness going to end?

No weasel words. Not: ‘Help make a blind man see.’ ‘Help us make other people like Asham see.’ ‘With your support, Help the Aged has performed 5,000 such operations: please help us to do more.’

No reference to the success of the charity. Almost nothing about the charity.

At no point is the reader asked to give to Help the Aged. The charity is simply the conduit that enables the donor to change the life of one man.

One person. One need. One solution. One donor engagement.

Cataracts strike thousands of elderly people in India and Africa, leaving them blinded and helpless.

A brief paragraph on the need.

Yet cataracts can be cured by a simple operation that costs as little as £10. (£100)

A brief paragraph on the solution,

Help the Aged are running ophthalmic programmes in India and Africa that are steadily eliminating as many cataracts as we have funds for – nearly 5,000 last year.

A brief paragraph that does a lot.

- On why Help the Aged is the right charity to deliver the solution. (Help the Aged was a new charity then, so needed to demonstrate its credentials.)

- This paragraph also introduces the bigger picture.

- It also, for the first time, gives a sense of urgency, but in an understated way, not a red rubber stamp: ‘URGENT’.

Money is desperately needed to support projects that tackle the root causes of the problem: poverty, bad hygiene, malnutrition.

A brief paragraph on the need for money, both for ‘the blind man’ and in the wider context. But the wider context is not put in a way that would distract from the single-minded proposition of making one blind man see.

And the second reference to urgency. An emotive ‘desperately needed’. Subtle, not in your face.

Please be as generous as you can, as soon as possible, because when blindness is the problem, prevention is the best cure of all.

A brief call to action.

Advertisement

- With the third, and final reference to urgency. ‘…as soon as possible.’ Again, understated.

- And the request is not for £10, but: ‘please be as generous as you can…’ Of course this was deliberate.No tick boxes with differing amounts. Starting with the lowest or starting with the highest? Three, or four? A large amount, for people who have just had a windfall? I know we have all tested all this and much, much more.Harold was putting the decision of how much to give in the hands of the donor.

Together, a complete case statement, in exactly 100 words.

The response coupon

And then, the response coupon. Paradoxically, given what’s above, the response mechanism starts ‘I want to make a blind man see.’, underlined gently.

At the risk of being accused of being over-analytical, I believe this is all very deliberate. The headline sets out the proposition. The text puts the amount in the hands of the donor, but, just as the donor is about to fill in the form, Harold reminds the donor of the proposition. Of wanting to make a blind man see.

Sheer brilliance.

And then: ‘Please accept my cheque/p.o. for £…’ No prompt. As I’ve said the decision of how much is totally open, in the hands of the donor. No amount too small to help.

In my view there is not a word too many. Or a word missing. Every word in every sentence in every paragraph in the whole ad is precisely crafted. There are few who do that today.

Harold Sumption

Harold was not an amateur fundraiser. Although his obituaries talk mainly of his charity work, Harold was a seasoned commercial advertising professional. He enjoyed a key role at several innovative UK advertising agencies, including chairman of the fashionable start-up MWK in the late 1970s. He applied his great commercial experience to the world of fundraising.

He knew precisely what he was doing.

I am not advocating that we go back to Harold’s simplicity, but we should think carefully about what we might learn from Harold’s approach and indeed what of his approach is still totally relevant in 2017. When the Commission on the Donor Experience reports in April, it will include much of Harold’s thinking, although the writer may not have realised it.

Today, the execution is dated. The thinking isn’t. We have moved too far away from that thinking. We may be right. But we may be wrong. At the very least, we should test our current thinking against Harold’s.

For those that are interested in Harold’s simple aphorisms, I have today posted a blog on 101 fundraising.

Giles Pegram CBE

© 2017 Giles Pegram CBE

With thanks to Ken Burnett.

See also: Ken Burnett and Tony Aldrich on SOFII.

Also on SOFII

The father of modern day fundraising: Harold Sumption

Harold Sumption the shy pioneer.